2022 ROME PRIZE FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENT

Read MoreIn the N.B.A., the Court and the Canvas Are Increasingly Intertwined

By Mike Vorkunov

Published: April 8, 2018

Artist William Villalongo, left, discussing one of his works of art with Caris LeVert and Gardy St. Fleur at the Susan Inglett Gallery in October. CreditDemetrius Freeman for The New York Times

Caris LeVert arrived at a mostly empty West Side art gallery for a private showing late last October. William Villalongo, an artist, walked around with him that evening, describing his dozen or so works hanging on the walls. LeVert, a second-year Nets guard, is a neophyte in the art world. His father, Darryl, had been a graphic designer and drawn family portraits, but LeVert was in unfamiliar territory.

Still, Villalongo and LeVert found common ground through the tour. “There’s not too much difference between artists and athletes,” Villalongo said. “It’s based on skill.”

There is also the creativity that both groups possess. Much the way a game cannot be replicated, each painting is one of a kind.

“The only difference is you guys,” Villalongo said of athletes, “make a lot more money.”

For LeVert, the evening was part of an immersion. He had recently begun learning more about art but was not yet intrepid enough to buy anything. For now, art is a burgeoning hobby. In time, though, it could lead him to become a collector.

N.B.A. players have grown more interested in art in recent years and created a new market of consumers and enthusiasts. Former Knick Amar’e Stoudemire has amassed a notable art collection and served as a league tastemaker. Grant Hill’s African-American art collection has been exhibited at museums. Former Suns guard Elliot Perry is known league-wide for his impressive trove.

“Guys have different ways of collecting and different reasons for collecting,” Ronnie Price, a 12-year N.B.A. veteran, said. “I don’t think that it’s as big of a secret as it used to be. I think guys are into learning more about their world. Because basketball players have an extremely creative mind and I think most basketball players you see with tattoos, they appreciate art. They have art all over their body.”

So what was once a small niche of N.B.A. collectors has flourished into something larger. Numbers are difficult to come by, but Price estimated that two players on each team he’s played for — he’s been with Sacramento, Utah, Phoenix, Portland, Orlando and the Los Angeles Lakers — have had collections. And in the middle, serving as a liaison to the art world, is the longtime New Yorker Gardy St. Fleur.

Born in Port-au-Prince, St. Fleur grew up with art as a central part of his life. His father collected Haitian masters and commissioned work for local artists. His family moved to Brooklyn when he was a child, and St. Fleur spent his adolescence and early adulthood learning from artists. He befriended Ionel Talpazan, the New York City artist famous for painting extraterrestrial life, worked as a studio manager for Villalongo and, he said, regularly grabbed coffee with Emmanuel Benador, an art dealer.

Caris LeVert studying artwork by William Villalongo. Credit: Demetrius Freeman for The New York Times

And he became just as interested in the artists as in their work.

“Why do they do the things that they do?” he said. “Fascinated with the way they think. As I get more information from them, I gravitate closer and closer to them. That helps me understand a little more.”

After a job out of college working in e-commerce, St. Fleur decided to follow his passion. Villalongo introduced him to Peggy Cooper Cafritz, who had a prestigious African-American art collection, and she gave him an assignment: Help her find new artists who were finishing graduate school.

Not long afterward, he decided to push into the art business full time. And from there came his involvement in the N.B.A. ecosystem, a relationship built in part from the days when St. Fleur would hang around the Rucker Park and West Fourth Street basketball courts in Manhattan, meeting people who eventually became player agents. Getting to know Deron Williams, the former Nets guard, became fruitful, too. Williams was looking to build an art collection, not just acquire a few pieces.

So St. Fleur got involved, and soon his name began to hopscotch around the league.

He has worked with Houston Rockets forward P. J. Tucker, Hall of Famer Alonzo Mourning and Yankees pitcher C. C. Sabathia, among others, he said. Knicks guard Courtney Lee was connected with him through the team, St. Fleur said, after he had previously built a relationship with Carmelo Anthony, the former Knicks star. N.B.A. veteran Dahntay Jones started talking to St. Fleur about art while he was working out at Manhattan’s Sky gym last summer, where Anthony held his popular “Hoodie Melo” scrimmages.

In his work, St. Fleur has tried to be as much teacher as salesman. He introduces athletes to artists, trying to break through the intimidation that affects some players. St. Fleur sends out newsletters to enlighten players, ships books to display different artists and styles, and texts photos of works to players if he believes one or more of them might be interested. Sometimes, he’s there to caution a player against overpaying.

You don’t need millions to buy art, he often says.

When Jay-Z released his latest album, “4:44,” St. Fleur was flooded with text messages. A song, “The Story of O. J.,” with its references to buying artwork, had served as a jolt to some players, reinforcing what St. Fleur had been telling them for years: that art can also be an investment and a way for generations to create something to pass down.

“When guys start understanding the history of families collecting,” St. Fleur said, “maybe it can be bigger than sports and who I am.”

Former Knick Amar’e Stoudemire, who has amassed a notable art collection, at Art Basel in Miami in December. Credit Daniel Arnold for The New York Times

This evolution all took a while. In the mid-1990s, when Perry was in the middle of his N.B.A. career, he was virtually alone as he started his collection.

He had turned to art almost by accident. In 1996, Perry was seated next to Darrell Walker, the former Knicks guard, on a long flight to Japan for an exhibition tour led by Charles Barkley. Walker asked him if he knew anything about art.

He did not.

The next season, Walker began helping Perry explore. When Perry came to New York, Walker called with instructions on which gallery to visit. When he went to Boston, Walker recommended a studio. Perry got to be so insatiable that he would arrive in a new city, drop his bags in his hotel room and go studio-hopping to find new works. He began reading, too, learning about Renaissance artists and American painters who emerged in the 1930s with the support of the federal Works Progress Administration.

Still, it took a year until Perry was comfortable enough to buy his first piece. Entering the art world had been overwhelming.

At first, Perry built a collection from works by African-American artists. Motivated by a quote in a catalog he had received at a showing of works owned by Walter O. Evans, a renowned African-American collector, Perry later decided to purchase only work from artists he could meet in person, get to know and support. He called Walker the day he decided to take that approach.

“This is a journey,” said Perry, who is now a limited partner and executive with the Memphis Grizzlies. “Even though you have the resources, that doesn’t mean anything. You still want to take your time. You want to buy the right pieces. You’regoing to make some mistakes, but that’s part of the journey.”

The heightened interest in art from N.B.A. players would seem to dovetail with their increased influence on American culture. And it has made art something of a conversation starter in N.B.A. locker rooms, where, not long ago, Lee, Michael Beasley and Jarrett Jack of the Knicks were discussing kre8artafax, an artist they discovered on Instagram.

“He’s like a basketball player,” Dahntay Jones said of kre8artafax. “He feels something every time he starts painting, so that’s just passion in its purest form. That’s part of what we do — passion about our game.”

The New Yorker "William Villalongo"

William Villalongo

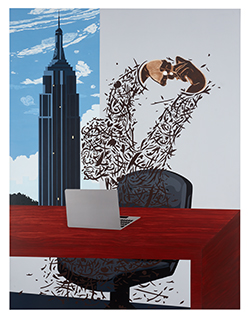

The men portrayed in the American artist’s new gut-punching collages and paintings are almost entirely composed of cuts. Sliced out of imported black velour paper, the swooshes, loops, and hearts are stark white; on painted wooden panels, they’re a mellower violet. With the addition of acrylic eyes, hands, and feet, these characters convey a dancerly élan—the figure in “Corner Office” flexes under a view of the Empire State Building, while the man in “Obertura de la Espora (Time Dancer)” wears a collaged necklace of African masks. However sprightly Villalongo’s works may appear, he is rendering trauma, and his men also convey something heavier. In “Free, Black and All American No. 3,” it’s the phrase “2.3 million incarcerated”; in the otherwise penumbral “Vanitas,” a silver tray holds rotting fruit and a photograph of the racist mass murderer Dylann Roof.

Through 9 December 2017

SUSAN INGLETT

522 W. 24th St., New York, N.Y.

212-647-9111

Making Out the Black Body in Swirling Images

When looking at the pieces in William Villalongo’s Keep On Pushing exhibition, the question I’m faced with is: How do these bodies cohere?

By Seph Rodney, 29 November 2017

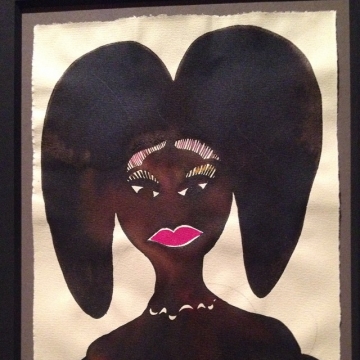

The figures in William Villalongo’s portraits mostly consist of a tumult of white negative space cut out of black velour paper. The shapes in the swirling, particulate cloud made to represent the body are odd, organic silhouettes that might be leaves and branches. In fact, Villalongo hints at that reading in three of the pieces in his exhibition Keep On Pushing at Susan Inglett gallery: the collages in the Free, Black and All American (2017) series, in which a bird hovers around or has settled on a chaotic pile that comes together enough to register as a person’s head. When looking at those pieces, and most others in the show, the question I’m faced with is: How does this body cohere? Asked another way: What unites these diverse forms into what I recognize as a body?

The work provides the answers. Anchoring each maelstrom are the body parts most evocative of agency: (brown) eyes that are the putative windows of the soul, (dark brown) hands that give us the ability to both invent tools and utilize them, and (dark brown) feet that make us mobile, so that we are not perpetually tied to whatever fate we were born to. Given these clues, I know I am dealing with a black body presented as an iconic object, all magpie disarray, but forming an intelligible whole.

But besides the appendages and organs, Villalongo also alludes to methods of socialization to show us what keeps the black body together. For example, there are the demands and responsibilities of a profession, as in the collage “Corner Office” (2017), where the figure has a white-collar job that entails sitting at a pristine desk accessorized by only a computer and a single skyscraper visible over his shoulder. The body is also held together by the requirements of social events, as in “Black Tie Affair” (2017), where the face is just that cutout filigree, plus the eyes, hands, and a bow tie.

Most of all, Villalongo suggests that it’s history that shapes the black body. In “Free, Black and All American no. 2,” the figure’s hands hold up a sign that reads “250 yrs slave; 152 yrs free.” This historical circumstance helps to make the black body just that: a black body — a heavily theorized, discursive construction that is pulled in several opposed directions at once: authenticity, fake-it-til-you-make-it performance, violence and conscientious objection to it, Christian religiosity and pre-modern belief systems, sexual delight and sexual revulsion. The list goes on. The key point here is that our shared history of slavery, of institutionalized violence and debasement, as destructive as it has been, is also constitutive. In addition to one’s occupation, mode of dress, or manner of speech, dark-skinned bodies in this time and place share this history and the resilience it has forced on us. Thus our bodies, while being schemes of competing claims, refuse to fly apart.

Keep On Pushing continues at Susan Inglett gallery (522 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through December 9.

Images:

William Villalongo, “25 Hour Cargo Piece” (2017) acrylic, paper collage, and velvet flocking on wood panel, 46 x 60 x 1 1/2 inches (all images by Argenis Apolinario and courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, New York)

William Villalongo, “Corner Office” (2017), acrylic, paper collage, and velvet flocking on wood panel, 46 x 60 x 1 1/2 inches

William Villalongo, “Black Tie Affair” (2017), acrylic, paper collage, and cut velour paper, 18 3/4 x 18 1/2 inches

USF's 'Black Pulp!' and 'Woke!' exhibits reframe African-American representation

By Maggie Duffy, Times Staff Writer // Wednesday, June 28, 2017 5:00am

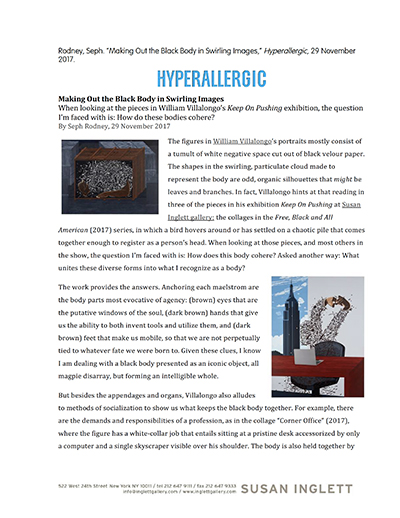

Renee Cox's Chillin with Liberty (1998) is part of the "Black Pulp!" exhibition at the University of South Florida's Contemporary Art Museum. Courtesy of Renee Cox

The concept of being "woke" is inextricably woven into the zeitgeist. To be truly woke, you have to be aware of not only current social injustices, but also the historical fight against prejudice.

While probably coined by Erykah Badu in 2008 in her song Master Teacher, "woke" and "stay woke" became closely affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement after the 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. That event prompted artists William Villalongo and Mark Thomas Gibson to curate "Black Pulp!" and "Woke!," now on view at the University of South Florida's Contemporary Art Museum.

The two exhibitions are presented in separate galleries. "Black Pulp!" takes you on a journey of African-American history through print media. "Woke!," which features Villalongo's and Gibson's artwork, picks up today.

View "Black Pulp!" first. The exhibit focuses on more than a century of print media created predominately by African-American artists, writers and publishers, displayed in cases, with works of contemporary art from leading artists strategically peppered in on the walls. "Black Pulp!" explores how African-Americans strove, and continue to reinvent the image so negatively painted by whites in the Jim Crow era, and gives a fairly comprehensive history of that struggle.

Villalongo and Gibson did an astounding job culling examples of print from important writers, scholars and artists, and there's plenty of information accompanying each piece to explain its historical significance.

There's a copy of The New Negro, Alain Locke's 1925 compilation of cultural criticism, art and literature. It was nearly the definitive text of the Harlem Renaissance, including writing by Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and W.E.B. Du Bois. The book gave rise to the discussion of self-determination among African-Americans. It includes illustrations by Aaron Douglas, a premier artist of the Harlem Renaissance, known for his African figures stylized in an Art Deco aesthetic. Douglas also illustrated the Harlem-based publications The Crisis and Opportunity (examples of both are included), which featured literature, politics and art, the goal being to present informed images of African-American life in the face of mainstream media's racist caricature of it.

Many of Aaron Douglas' illustrations are included in the show. While he was a prominent artist of his era who was exploring cubism and primitivism at the same time Picasso was, he's certainly not as well known. I'd never heard of him until well into my art history degree, during a class in 20th century art.

The exhibit includes many iconic covers of the Black Panther Party newspaper, illustrated by Emory Douglas, the party's minister of culture. By presenting the book Women Builders (1931), a number of significant histories are revealed. Written by Sadie Iola Daniel and illustrated by influential illustrator Lois Mailou Jones, the book features the biographies of seven African-American women who founded institutions for their communities. It was published by the Associated Publishers, founded by Carter G. Woodson, whose mission was to collect then almost nonexistent written African-American history. Woodson's endeavor is what led to the creation of Black History Month.

"Black Pulp!" also explores the theme of heroes. There weren't many, or really any, examples of black heroes in mainstream comic strips and comic books, so artists had to create their own. The exhibition includes a number of examples of African-American comics, including Orrin C. Evans' All-Negro Comics from 1947. We see the first black cowboy in a comic in Don Arenson's Lobo from 1965, also the first African-American standalone comic book. Billy Graham, who wrote Luke Cage and Black Panther, was the first African-American artist to work for Marvel Comics.

That theme is bolstered by Renee Cox's Chillin With Liberty (1998). The Cibachrome print features Cox perched atop the Statue of Liberty's crown, dressed as the superhero Raje, a character she invented to address the dictated roles of African-American women.

In response to the lack of black superheroes, Kerry James Marshall creates his own in the comic strip Dailies From Rythm Mastr (2010) by conjuring the Seven African Powers, Yoruban gods, reimagined as Nat Turner, the slave who led the famed 1831 rebellion.

The contemporary art portion of "Black Pulp!" continues the conversation. Acclaimed artist Kara Walker's Alabama Loyalists Greeting the Federal Gun-Boats is part of a series she did using illustrations from Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). She screenprints silhouettes of stereotypical caricatures of African-Americans on them, large and in the foreground. The silhouette of a woman falling disrupts the scene of a crowd of people eagerly welcoming the arrival of Confederate war vessels.

While "Black Pulp!" deals with the representation of the black figure, in "Woke!" Villalongo addresses the physical body. Two graphic pieces use the language of Black Lives Matter and Eric Garner, who died from a police officer's choke hold: You Matter and We Can't Breathe. Each letter is printed on a page from a coloring book of the human anatomy, including the skin, the central nervous system and the mechanics of breathing and swallowing. The need to point out that African-Americans are living, breathing human beings and therefore should matter is heartbreaking.

Villalongo expands the theme of the body in four large-scale paintings called The Four Seasons. Each painting focuses on a black female figure that takes the concept of "nude" to the next level. Through the skin we can see bones, nerves, the brain, heart and digestive system. They're framed in foliage of the corresponding season, bordered in designs reminiscent of Matisse's plant and flower motifs. This was probably intentional, as Villalongo is seeking to reframe art history and Western art by using black women as the subject, instead of the pervading white female nude. He uses the seasons to illustrate the change he wishes to see and also as a reminder of how history repeats itself.

Gibson's pieces in "Woke!" are selections from a previous exhibition he had called "Some Monsters Loom Large." His painting Turnt Up shows a giant werewolf arm, skin ripping off to reveal the furry, clawed paw clenching a fist beneath. It could be interpreted that, like the change the werewolf goes through, so does the awareness of how unequal things really are. When another violent act against black people goes unpunished, the beast awakens, moved to protest. Then the curse ends, and the man wakes up, amnesic. Until the next time.

Gibson's The Last Dance is six drawings of an apocalypse, using animal figures to wage the battle between good and evil. Dog police and skeletons brutalize wolf-men that have been protesting. In one scene they're trampling a banner that just shows the word "matter." But in another, the wolf figure is a cavalry officer on horseback, led by another wolf-angel blowing a horn and accompanied by the same skeletons. A sign reads, "The end is nigh." That this figure is both victim and perpetrator may suggest something about the nature of this American cultural crisis. Artist and critic Robert Storr writes in an essay about this piece, "So if he is 'Everyman,' then every man is his own biggest problem."

The scene doesn't seem to end well.

Contact Maggie Duffy at mduffy@tampabay.com.

Which Artist Should Create Obama’s Official Presidential Portrait?

In a perfect world, who would be the artist that captures the likeness of Obama for his official portrait?

Recently, J.A. Boyd II, a youth pastor for a Baptist church in Newnan GA, tweeted an image of what he proclaimed to be the “official White House painting” of former US President Barack Obama. Boyd’s accompanying paean in praise of the painting is a single word: “BRUH!!!!”

Obama does look resplendent in the beige suit he once famously wore to a press conference in 2014, with just the hint of a smile creasing the area around his mouth. A Dutch artist, Edwin van den Dikkenberg, who has made that portrait in oil, has skillfully apprehended Obama’s combination of scholarly aloofness, confidence, and openness to being charmed. In this image there is also the resolute idealism, and curiosity that when I saw him in public appearances would often easily slide into a quizzical grin somewhere between empathic embarrassment on someone else’s behalf and outright dismissal as unworthy of further engagement. It is a striking image, but reportedly this is not the official White House portrait.

Still, it made me think about what contemporary artist would do best with this assignment. Of course, I immediately imagined Chris Ofili, the heavily stylized watercolor portraits he made mostly of women in the late 1990s. Ofili would give Obama back that superhero quality that initially imbued his presidency, making him an iconic black man in a tie-dyed dashiki, all coffee-with-milk brown skin and high forehead with gleaming eyes.

Johanna on Chris Ofili Watercolor Chris Ofili’s Muse serieWilliam

Better yet, Mickalene Thomas would transform the cool professor into a funkafied, stone cold, groovy cat reclining on a chaise lounge in the oval office, the walls doused in psychedelic patterns and sparkles. Though Thomas most often employs her powers of bringing her subjects’ sexiness to the surface with women, she might be talked into doing the same with the former president, turning him into the dancer he sometimes revealed himself to be: giving a little shoulder shimmy and a two-step, gray hair rendered in glitter like an astral field.

Kehinde Wiley is also an option. Of course, his portrait accomplished in the style of courtly painting would gives us the triumphant Obama, the Nobel prize winner, the man to pull us back from the brink of financial meltdown. However, the drawbacks are that such a portrait would only emphasize that confidence that too often was read as haughtiness, and if Wiley works like he usually does the overall physical comportment might look too staged, too stiff.

Dawoud Bey, “Barack Obama” (2007), pigment print 30 X 24 inches (© Dawoud Bey )

Dawoud Bey could make a wonderfully intimate photograph of Obama, since they are already familiar with each other after Bey took a picture of the then pre-gray senator from Illinois back in 2007. His portrait would be staid, quietly dignified, but forthright — letting through the weariness and perhaps even the inner fortitude of the man who throughout the tenure of his presidency was consistently publicly called a Muslim terrorist from Kenya.

William Villalongo, “Barack and Nefertiti in the Vela Supernova Remnant” (2009), hubble telescope poster, velour paper, mirrored mylar, acrylic paint, 30 x 24 in (photo © William Villalongo, courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC)

The artist William Villalongo could actually dig into those African roots, via Obama’s father (Barack Hussein Obama, Sr. was a Kenyan senior governmental economist), back to a storied past that tends to conflate all the technological achievements made on the continent and shunt them through the legends and accounts of life in Egypt. Villalongo did that digging soon after Obama’s historic election, taking an image of the president and making him a kind of celestial mélange with Nefertiti, an Egyptian queen, who along with her husband Akhenaten, an Egyptian Pharaoh, was known for fomenting a profound change in religious practices within Egypt. Despite all the shortcomings of his presidency, such as portrait would affirm the fact that change did indeed occur with his presidency.

Lastly, we could stretch the boundaries of the portrait and instead of a painting or photograph, make it a black-and-white film montage by Steve McQueen, in which there is a long shot of him standing by the window in the White House, peering out in silence while in the foreground a clump of advisers and cabinet members talk among themselves, until Obama turns and walks towards them and the camera and the part like the Red Sea and they are suddenly quiet, waiting for him to speak.

The Push Back: Black Pulp! and Woke! at USF CAM

Getting to the roots of black print imagery to get to liberation.

Caitlin Albritton – June 13, 2017

Walking amongst a bustling opening reception at USFʼs Contemporary Art Museum, through the noise a visitorʼs voice stated clearly: “This is an important exhibition.” And that it is.

By now, we all realize the importance of #BlackLivesMatter, but Black Pulp! puts the grassroots nature of this movement into historical perspective. Artists-curators William Villalongo and Mark Thomas Gibson (who have a two-person exhibition Woke! simultaneously at CAM) have dug up the past to share an unprecedented compilation of graphics and image-making by black artists and publishers from the last century.

Curation of the show came about as Villalongo and Gibson (longtime friends with ties to Cooper Union and Yale) were discussing figuration, specifically regarding Kara Walkerʼs exhibition A Subtlety at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn (a.k.a. The Marvelous Sugar Baby).

“It [the sculpture] was so audacious and I was trying to understand why Kara Walkerʼs work was so hard to talk about,” Gibson says during the artist talk led by Margaret Miller, theDirector of the Institute for Research in Art at USF, last Friday night.

From there, the two artists discussed the roles of humor, satire, appropriation and how to approach these difficult conversations surrounding black representation in contemporary art. By focusing on illustrative and print-based work instead of painting, the topic of discussion shifts to accessibility, as well as affordability, and how these factors play into mass audiencesʼ ability to connect with the work.

Showcasing historical works in cases at the center of the room while featuring contemporary pieces on the surrounding walls, Villalongo and Gibson have traced the lineage of pulp works based in artist-run magazines, comics, books, vinyl covers and posters (as well as fine art prints and other works on paper). From Black Panther Party memorabilia to black poetry, all of these methods of underground publishing serve as pushback against outside representations of the black experience, to turn image culture around and combat it by flooding it with their voices.

Billy Grahamʼs Luke Cage, Hero for Hire comics provide a springboard into many of the contemporary works by making black figures not as inferior sidekicks to white companions, but heroic protagonists in their own right. From these examples you can see the influence on current artists like Kerry James Marshall or Trenton Doyle Hancock as they create their own characters, mythologies, narratives and realities.

Renee Coxʼs “Chillin with Liberty” feels even more powerful than ever. Dressed as her heroic character (or perhaps alter ego) Rajé, sheʼs relaxing in a quiet moment between battling crime (like saving Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben from their oppressive food stereotypes). Sitting atop Lady Libertyʼs crown looking out with a stoic expression, it makes you wonder if she already sees the hardships ahead. Regardless, she serves as a symbol of black emancipation by providing positive forms of self-representation.

On the other side of the gallery youʼll find Woke!, a selection of work by Villalongo and Gibson that deals with American atrocity and the black body in a physical way. Both artists say their worlds changed after Eric Gardner and the Ferguson protests.

If thereʼs a must-see exhibition this summer, itʼs undoubtedly Black Pulp!, a show worth repeated visits. From early black newspapers and 'zines to the current use of social media hashtags and graphics, everyday forms of aesthetics can be sites of resistance, recontextualization and representation for the black community to capitalize on for self-definition and self-expression.

John Legend, Foo Fighters, Bjork On New '7-Inches for Planned Parenthood' Box Set

The project also includes comedians (including Sarah Silverman, Janeane Garofalo, Tig Notaro, Aparna Nancherla and Margaret Cho), writers and activists (Margaret Atwood, dream hampton, Dr. Willie Parker and Heather McGhee) and the work of visual artists (Angela Pilgrim, Shepard Fairey, Mark Fox, Rashid Johnson and William Villalongo among others).

Read MoreBrooklyn Artists Harness the Power of Bodies

"The other artist in the show whose work seems most evocative of the theme is William Villalongo. His portraits consist of cut velour paper on matte board and take a very different approach . . . "

Read More16 Artists Who Made Sure Black Lives Mattered at Art Basel Miami Beach

"William Villalongo sold out of his cut-paper artwork the first day of the Untitled Art Fair."

Read MoreM/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking-2

"My figures toil between various histories and an endless natural world conscious of painting as their condition of being. These new works meditate on the Black male presence in society as a figure shifting in out of visibility."

Read MorePhotos: BRIC Biennial, V. II Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights Edition

"The BRIC Biennial: Volume II, Bed-Stuy/Crown Heights Edition kicked off on November 10, featuring the work of local artists surveying the rapidly changing neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights."

Read MorePi Artworks London Presents: American Histories

"As part of its Curatorial Season, curated by Alexandra Schwartz, Pi Artworks London presents American Histories, an exhibition that aims to explore cultural history through figurative drawing. Working solely through the medium of drawing, the exhibition comprises of work by Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze, Kenseth Armstead, Firelei Bäez, Maria Berrio, Chitra Ganesh, Fay Ku, Lina Puerta, Frohawk Two Feathers, William Villalongo . . ."

Read MoreLife Lived in Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights Surveyed at BRIC Biennial, V.II

"The BRIC Biennial: Volume II, Bed Stuy/Crown Heights Edition is the largest and most ambitious exhibition organized by BRIC to date, highlighting the significance of Brooklyn as the place where New York artists create work and develop their careers."

Read MoreContemporary Artists Animate Masquerade Traditions

When W.E.B. Dubois advanced the "life behind the veil” and “double consciousness” concepts in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), he was referring to African American experiences of separation and invisibility that also characterize the act of masking. In his poem, “We Wear the Mask,” Paul Laurence Dunbar graphically described the tradition of masquerade in African Diasporic life [...]

Read More‘Disguise: Masks and Global African Art,’ Where Tradition Meets Avant-Garde

Then, largely thanks to Picasso’s electrifying encounter with African masks around 1907 and the colleagues who followed suit, Europeanized African aesthetics became integral to Modern art. That development is skewered here by William Villalongo’s neatly made collages. In several, an African mask cut from a photograph has been glued over a woman’s head in a reproduction of a painting by a European or an American, from a zaftig nude by Renoir to a pinup by the Pop artist Mel Ramos.

Read MoreA score of young artists recover and renew the rebel power of African masks

Other proposals are those of the AmericanWilliam Villalongo (1975), who builds collages in which he inserts traditional masks over classic European baroque prints, and Brendan Fernandes (born in Kenya in 1979 and resident in Canada) opted for the proposal of neon masks.

Read MoreThe Brooklyn Museum’s African Mask Show Is a Complex, Powerful Exploration of Identity

These artists help show us that African masks are not lifeless objects made only to be looked at, but rather are potent, animate forms with active uses. In turn, the masks show us that the contemporary artists’ works exist on a long continuum of African mask-making and masquerade, which Dumouchelle describes as a “genre that is a platform for artistic creativity and engagement with the issues of its time, and of our time.”

Read MoreAt the Brooklyn Museum, African Masks Take On A Fresh Glow

From performances during the Stone Age to being co-opted by Picasso and Matisse, African masks have been part of art's vocabulary for centuries, although today's iterations have a decidedly fresher face. "Disguise: Masks and Global African Art," opening Friday at the Brooklyn Museum, offers 25 contemporary African artists' takes on the medium

Read MoreA 2014 work by Adejoke Tugbiyele

‘Disguise,’ of Masks and Global African Art

“Disguise: Masks and Global African Art” expands upon a show organized by the Seattle Art Museum, featuring more than 25 contemporary artists from Africa and of African descent from around the world, often representing them with several works each — photography, installation, drawing, sculpture and video.

Read More