When looking at the pieces in William Villalongo’s Keep On Pushing exhibition, the question I’m faced with is: How do these bodies cohere?

By Seph Rodney, 29 November 2017

The figures in William Villalongo’s portraits mostly consist of a tumult of white negative space cut out of black velour paper. The shapes in the swirling, particulate cloud made to represent the body are odd, organic silhouettes that might be leaves and branches. In fact, Villalongo hints at that reading in three of the pieces in his exhibition Keep On Pushing at Susan Inglett gallery: the collages in the Free, Black and All American (2017) series, in which a bird hovers around or has settled on a chaotic pile that comes together enough to register as a person’s head. When looking at those pieces, and most others in the show, the question I’m faced with is: How does this body cohere? Asked another way: What unites these diverse forms into what I recognize as a body?

The work provides the answers. Anchoring each maelstrom are the body parts most evocative of agency: (brown) eyes that are the putative windows of the soul, (dark brown) hands that give us the ability to both invent tools and utilize them, and (dark brown) feet that make us mobile, so that we are not perpetually tied to whatever fate we were born to. Given these clues, I know I am dealing with a black body presented as an iconic object, all magpie disarray, but forming an intelligible whole.

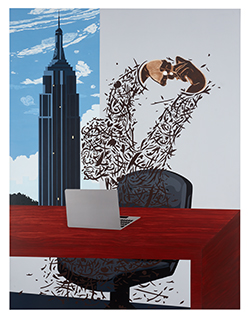

But besides the appendages and organs, Villalongo also alludes to methods of socialization to show us what keeps the black body together. For example, there are the demands and responsibilities of a profession, as in the collage “Corner Office” (2017), where the figure has a white-collar job that entails sitting at a pristine desk accessorized by only a computer and a single skyscraper visible over his shoulder. The body is also held together by the requirements of social events, as in “Black Tie Affair” (2017), where the face is just that cutout filigree, plus the eyes, hands, and a bow tie.

Most of all, Villalongo suggests that it’s history that shapes the black body. In “Free, Black and All American no. 2,” the figure’s hands hold up a sign that reads “250 yrs slave; 152 yrs free.” This historical circumstance helps to make the black body just that: a black body — a heavily theorized, discursive construction that is pulled in several opposed directions at once: authenticity, fake-it-til-you-make-it performance, violence and conscientious objection to it, Christian religiosity and pre-modern belief systems, sexual delight and sexual revulsion. The list goes on. The key point here is that our shared history of slavery, of institutionalized violence and debasement, as destructive as it has been, is also constitutive. In addition to one’s occupation, mode of dress, or manner of speech, dark-skinned bodies in this time and place share this history and the resilience it has forced on us. Thus our bodies, while being schemes of competing claims, refuse to fly apart.

Keep On Pushing continues at Susan Inglett gallery (522 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through December 9.

Images:

William Villalongo, “25 Hour Cargo Piece” (2017) acrylic, paper collage, and velvet flocking on wood panel, 46 x 60 x 1 1/2 inches (all images by Argenis Apolinario and courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, New York)

William Villalongo, “Corner Office” (2017), acrylic, paper collage, and velvet flocking on wood panel, 46 x 60 x 1 1/2 inches

William Villalongo, “Black Tie Affair” (2017), acrylic, paper collage, and cut velour paper, 18 3/4 x 18 1/2 inches