By Maggie Duffy, Times Staff Writer // Wednesday, June 28, 2017 5:00am

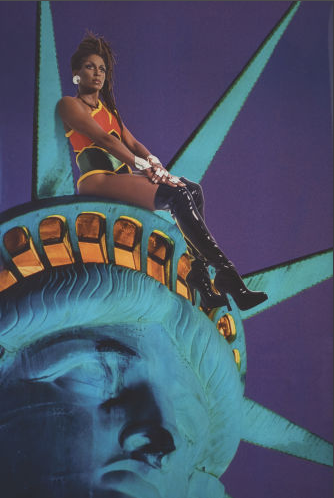

Renee Cox's Chillin with Liberty (1998) is part of the "Black Pulp!" exhibition at the University of South Florida's Contemporary Art Museum. Courtesy of Renee Cox

The concept of being "woke" is inextricably woven into the zeitgeist. To be truly woke, you have to be aware of not only current social injustices, but also the historical fight against prejudice.

While probably coined by Erykah Badu in 2008 in her song Master Teacher, "woke" and "stay woke" became closely affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement after the 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. That event prompted artists William Villalongo and Mark Thomas Gibson to curate "Black Pulp!" and "Woke!," now on view at the University of South Florida's Contemporary Art Museum.

The two exhibitions are presented in separate galleries. "Black Pulp!" takes you on a journey of African-American history through print media. "Woke!," which features Villalongo's and Gibson's artwork, picks up today.

View "Black Pulp!" first. The exhibit focuses on more than a century of print media created predominately by African-American artists, writers and publishers, displayed in cases, with works of contemporary art from leading artists strategically peppered in on the walls. "Black Pulp!" explores how African-Americans strove, and continue to reinvent the image so negatively painted by whites in the Jim Crow era, and gives a fairly comprehensive history of that struggle.

Villalongo and Gibson did an astounding job culling examples of print from important writers, scholars and artists, and there's plenty of information accompanying each piece to explain its historical significance.

There's a copy of The New Negro, Alain Locke's 1925 compilation of cultural criticism, art and literature. It was nearly the definitive text of the Harlem Renaissance, including writing by Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and W.E.B. Du Bois. The book gave rise to the discussion of self-determination among African-Americans. It includes illustrations by Aaron Douglas, a premier artist of the Harlem Renaissance, known for his African figures stylized in an Art Deco aesthetic. Douglas also illustrated the Harlem-based publications The Crisis and Opportunity (examples of both are included), which featured literature, politics and art, the goal being to present informed images of African-American life in the face of mainstream media's racist caricature of it.

Many of Aaron Douglas' illustrations are included in the show. While he was a prominent artist of his era who was exploring cubism and primitivism at the same time Picasso was, he's certainly not as well known. I'd never heard of him until well into my art history degree, during a class in 20th century art.

The exhibit includes many iconic covers of the Black Panther Party newspaper, illustrated by Emory Douglas, the party's minister of culture. By presenting the book Women Builders (1931), a number of significant histories are revealed. Written by Sadie Iola Daniel and illustrated by influential illustrator Lois Mailou Jones, the book features the biographies of seven African-American women who founded institutions for their communities. It was published by the Associated Publishers, founded by Carter G. Woodson, whose mission was to collect then almost nonexistent written African-American history. Woodson's endeavor is what led to the creation of Black History Month.

"Black Pulp!" also explores the theme of heroes. There weren't many, or really any, examples of black heroes in mainstream comic strips and comic books, so artists had to create their own. The exhibition includes a number of examples of African-American comics, including Orrin C. Evans' All-Negro Comics from 1947. We see the first black cowboy in a comic in Don Arenson's Lobo from 1965, also the first African-American standalone comic book. Billy Graham, who wrote Luke Cage and Black Panther, was the first African-American artist to work for Marvel Comics.

That theme is bolstered by Renee Cox's Chillin With Liberty (1998). The Cibachrome print features Cox perched atop the Statue of Liberty's crown, dressed as the superhero Raje, a character she invented to address the dictated roles of African-American women.

In response to the lack of black superheroes, Kerry James Marshall creates his own in the comic strip Dailies From Rythm Mastr (2010) by conjuring the Seven African Powers, Yoruban gods, reimagined as Nat Turner, the slave who led the famed 1831 rebellion.

The contemporary art portion of "Black Pulp!" continues the conversation. Acclaimed artist Kara Walker's Alabama Loyalists Greeting the Federal Gun-Boats is part of a series she did using illustrations from Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). She screenprints silhouettes of stereotypical caricatures of African-Americans on them, large and in the foreground. The silhouette of a woman falling disrupts the scene of a crowd of people eagerly welcoming the arrival of Confederate war vessels.

While "Black Pulp!" deals with the representation of the black figure, in "Woke!" Villalongo addresses the physical body. Two graphic pieces use the language of Black Lives Matter and Eric Garner, who died from a police officer's choke hold: You Matter and We Can't Breathe. Each letter is printed on a page from a coloring book of the human anatomy, including the skin, the central nervous system and the mechanics of breathing and swallowing. The need to point out that African-Americans are living, breathing human beings and therefore should matter is heartbreaking.

Villalongo expands the theme of the body in four large-scale paintings called The Four Seasons. Each painting focuses on a black female figure that takes the concept of "nude" to the next level. Through the skin we can see bones, nerves, the brain, heart and digestive system. They're framed in foliage of the corresponding season, bordered in designs reminiscent of Matisse's plant and flower motifs. This was probably intentional, as Villalongo is seeking to reframe art history and Western art by using black women as the subject, instead of the pervading white female nude. He uses the seasons to illustrate the change he wishes to see and also as a reminder of how history repeats itself.

Gibson's pieces in "Woke!" are selections from a previous exhibition he had called "Some Monsters Loom Large." His painting Turnt Up shows a giant werewolf arm, skin ripping off to reveal the furry, clawed paw clenching a fist beneath. It could be interpreted that, like the change the werewolf goes through, so does the awareness of how unequal things really are. When another violent act against black people goes unpunished, the beast awakens, moved to protest. Then the curse ends, and the man wakes up, amnesic. Until the next time.

Gibson's The Last Dance is six drawings of an apocalypse, using animal figures to wage the battle between good and evil. Dog police and skeletons brutalize wolf-men that have been protesting. In one scene they're trampling a banner that just shows the word "matter." But in another, the wolf figure is a cavalry officer on horseback, led by another wolf-angel blowing a horn and accompanied by the same skeletons. A sign reads, "The end is nigh." That this figure is both victim and perpetrator may suggest something about the nature of this American cultural crisis. Artist and critic Robert Storr writes in an essay about this piece, "So if he is 'Everyman,' then every man is his own biggest problem."

The scene doesn't seem to end well.

Contact Maggie Duffy at mduffy@tampabay.com.